Tree Searching

June 22, 2024

Position tree searching using the alpha-beta algorithm, quiesence search, and move ordering

Given unlimited time, finding the best move in any position would be done by checking down every possible tree of positions, where moves are continuously made until the game is either decided in a win, loss, or draw.

Sadly, this is just not possible due to how quickly the number of calculations grows. Since the the number of positions to consider grows exponentially, these calculations quickly become unmanageable. After getting to a depth of just 10 half-moves, we are looking at about 70 trillion positions. After 15, this becomes 2 sextillion, or 2 * 1021.

So to make an engine that is useful, we need to heavily trim down on these calculations. Some options we have are:

- Estimate the strength of a position

- We have implemented this in the previous section, where we went over an

evaluation()function.

- We have implemented this in the previous section, where we went over an

- Speed up the searching through the tree

- We will implement the alpha-beta search algorithm, which uses some logic to trim extra branches.

Alpha-Beta Search

Minimax

Before we get into alpha-beta, we must first understand the Minimax algorithm, which makes decisions based on the best move for the opponent.

In the context of our chess engine, it starts at the position we are in, and searches through every possible move up to a certain depth. After reaching the max depth, the strength of the position is estimated using evaluate(). As we go, we store the best move found and return that best move after searching through all options.

Logically, we can think of what is going on as follows, say White is to move:

Whitewants to make a move, so we considerBlack's best move in response to each move.Blackwill then want to make a best move, consideringWhite's best move in response to each move.- ...continue on until we reach the max depth.

- After we have searched deep enough, the strength of a position is determined by running

evaluate().

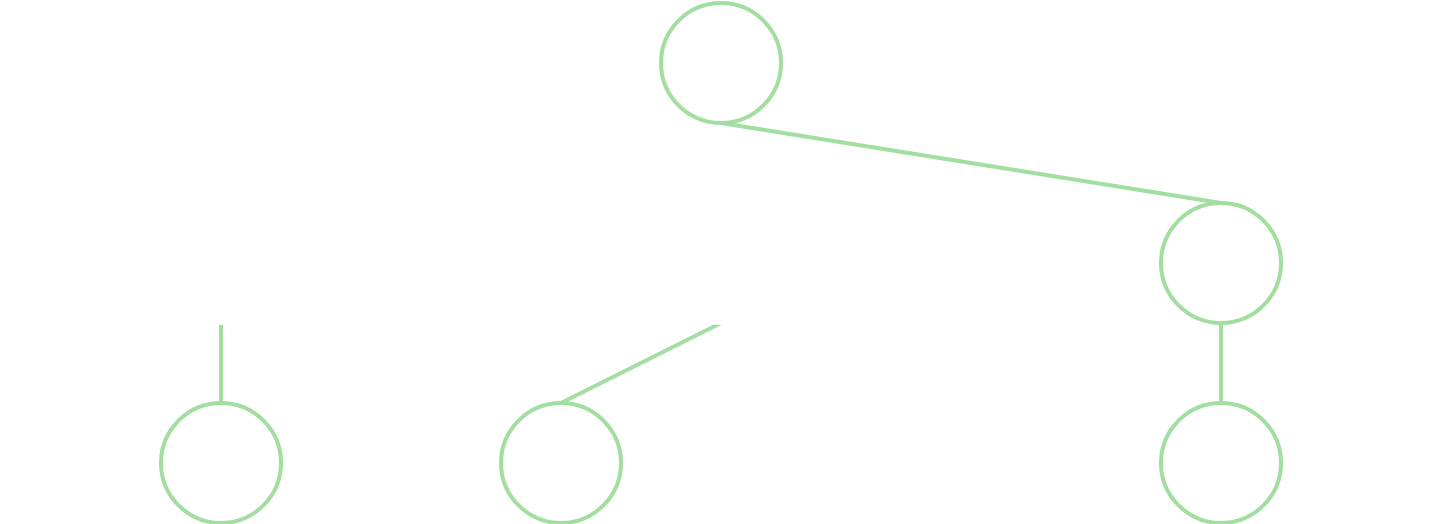

Graphically, at a depth of 2, the tree can be represented as:

Moves are made to a max depth, where they are then evaluated. At each level, a move is chosen based on what is worst for the opponent, then negated because a negative evaluation for the opponent is positive for us, and vice-versa.

If code is more your thing, here is snippet summarizing Minimax:

type Score = i16;

fn minimax(&mut board: Board, depth: u8) -> Score {

// base case: at max depth, evaluate position

if depth == 0 {

return evaluate(board);

}

let mut best = Score::MIN;

// recursively search and choose the best option

for mov in board.generate_moves() {

board.make_move(mov);

// negate score, because evaluation is relative to moving color

// however good/bad the opponent's evaluation is must be reversed for us

let score = -minimax(board, depth - 1);

// update best move so far

best = best.max(score);

board.unmake_move(mov);

}

best

}

Branch Trimming

Now, we move onto the alpha-beta search algorithm, which is an improvement on Minimax that removes branches deemed too good or too bad.

It is easiest to understand alpha-beta by going through an example first:

- Say we are

Whiteand looking for a move to make. We check through the entire subtree for our first move,move_a, and determine that this would lead to an even position. - Moving onto the second option,

move_b, while checking throughBlack's responses to this, we find thatBlackcould take a piece of ours and be at an advantage. - Having this knowledge, we can just completely forget about the rest of the search tree for

move_b, because by making this move,Blackwould definitely be at an advantage. We would always just choosemove_aovermove_b.

To allow for this kind of pruning, we keep a lower bound, alpha, which is updated as we go and used to trim branches that would be too bad for us.

We must also keep an upper bound, beta, which is be used to trim branches that are too good that the opponent wouldn't allow the move to even be made. Think of the opponent's view, where if they see we can make a great move leading to a worse position than their lower bound, they would trim it anyways.

Both alpha and beta are swapped with as we travel down the move tree, as one color's upper bound corresponds to the other color's lower bound.

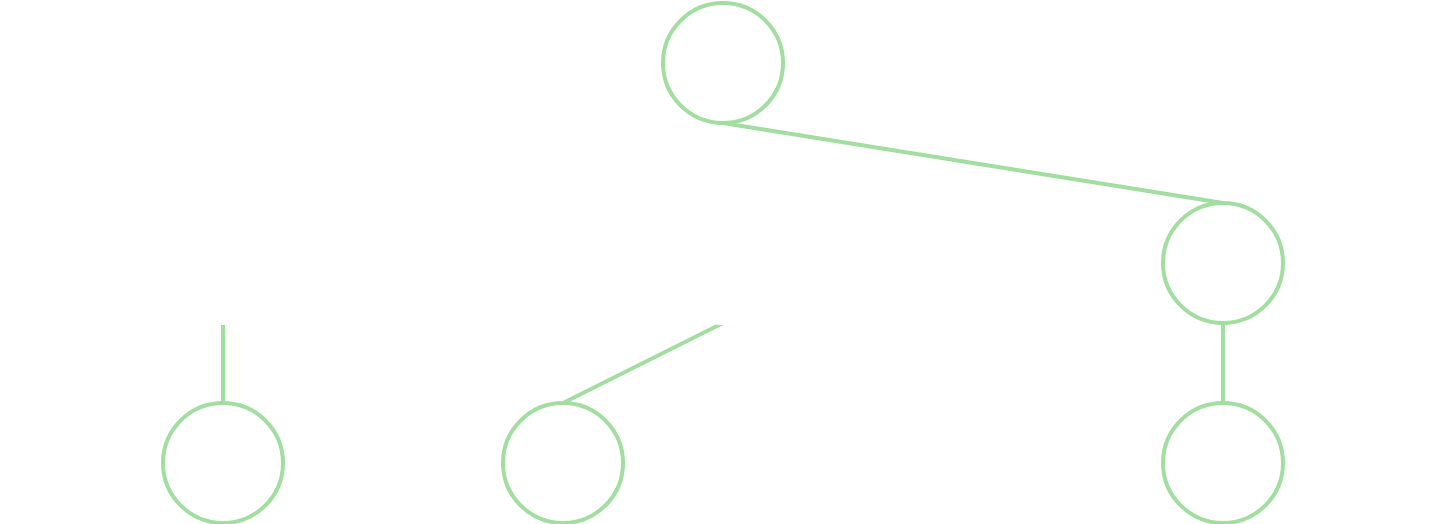

Let's examine the improved alpha-beta tree, working from the same Minimax example:

After searching through the first move subtree, we notice the score would be +100 for the opponent. Moving onto the next move, the first option checked would at least allow the opponent to be +300, already worse than our previous lower bound of +100. So, we just trim that entire branch and continue on, saving us some evaluate() calls.

This is a simple example with a depth of only 2. The time saved exponentially increases with the depth, where each of those single nodes would have entire subtrees worth of evaluations.

Again, a snippet summarizing the alpha-beta algorithm:

def alpha_beta(board: &mut Board, mut alpha: Score, beta: Score, depth: u8) -> Score {

if depth == 0 {

return evaluate(board);

}

for mov in board.generate_moves() {

// same here as before

board.make_move(mov);

// same idea, reverse evaluation for opponent

// also use negated alpha/beta but reversed

let score = -alpha_beta(board, -beta, -alpha depth - 1);

board.unmake_move(mov);

// if this move is better than opponent's best move,

// this will be trimmed later on, might as well do it now

if score >= beta {

return beta;

}

// update current best move

alpha = alpha.max(score);

}

// return our best case score value

alpha

}

Improvements

As with evaluation, there is a lot of room for improvement, let's explore some techniques.

Quiescence Search

With our current evaluate() function, there is one glaring issue. Notice how the evaluation function is only checking material value and position, and our search algorithm only goes to a certain depth. We could end searching on a move that has a high evaluation score for us, but actually blunders a piece the very next move.

To prevent this from happening, we need a way to "stabilize" the position. Quiescence search is an extra step before we evaluate in the alpha-beta search that does just this. Its purpose is to extend the search along any paths that have captures available, until we reach only quiescent (or quiet) positions.

The implementation for quiescence search is very similar to alpha_beta(), with just a few key differences:

- Only capturing moves are generate and searched

- Otter achieves this by generating moves as usual and filtering out those without matching capture

MoveFlags. - In more efficient engines, this is done fully within the move generator, so that only capturing moves are generated.

- Otter achieves this by generating moves as usual and filtering out those without matching capture

- Before searching captures, assess the current board evaluation

- This is needed in case there are no capturing moves, as a score must be returned to the calling search function.

- This also gives us a safe

alphalower bound to start with, because in nearly all cases, taking an opponent's piece is good for us. - We can also run this against

betaand possibly trim the branch, in case this position is too good for us that the opponent would just forget this move.

- There is no

depthparameter- Keeping a

depthvalue is not required, as we just continue searching until the position is fully quiet, no captures available.

- Keeping a

fn quiesce(board: &mut Board, mut alpha: Score, beta: Score) -> Score {

// first determine current evaluation and check vs alpha and beta

let curr_score = evaluate(board);

if curr_score >= beta {

return beta;

}

alpha = alpha.max(curr_score);

// run through all captures, if any, same process as alpha-beta search

for mov in board.generate_captures() {

board.make_move(mov);

let score = -quiesce(board, -beta, -alpha);

board.unmake_move();

if score >= beta {

return beta;

}

alpha = alpha.max(score);

}

alpha

}

Move Ordering

To get the fullest benefit of alpha-beta, we want to trim as many branches as possible. If we aren't trimming any branches, there is no real difference between alpha_beta() and minimax().

Notice that the case for trimming a branch is when we go through a good move first. Having a higher alpha lower bound earlier on gives us a better chance of trimming branches later. Conversely, if we go through moves worst to best, we end up searching the branches we should be trimming.

The idea of move ordering is to spend a little extra time and sort generated moves from best to worst, so that we can save more time later by trimming the branches from bad move trees. But how do we figure out what moves are better than others?

The process, similar to evaluate(), depends upon the engine, but Otter considers a few simple cases:

- Prefer attacking a higher value opposing piece with a lower value friendly piece

- Prefer pawn promotions

- If the move was previously found to be the best option, order it first

- How would this actually happen? Check out the next section to see how board positions and their best moves are cached for later use.